Architects, Anthills, and AI: A Nobel Prize’s Lesson on Scientific Progress

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry has been awarded to Susumu Kitagawa, Richard Robson, and Omar M. Yaghi for their creation of an entirely new class of materials: metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) [1].

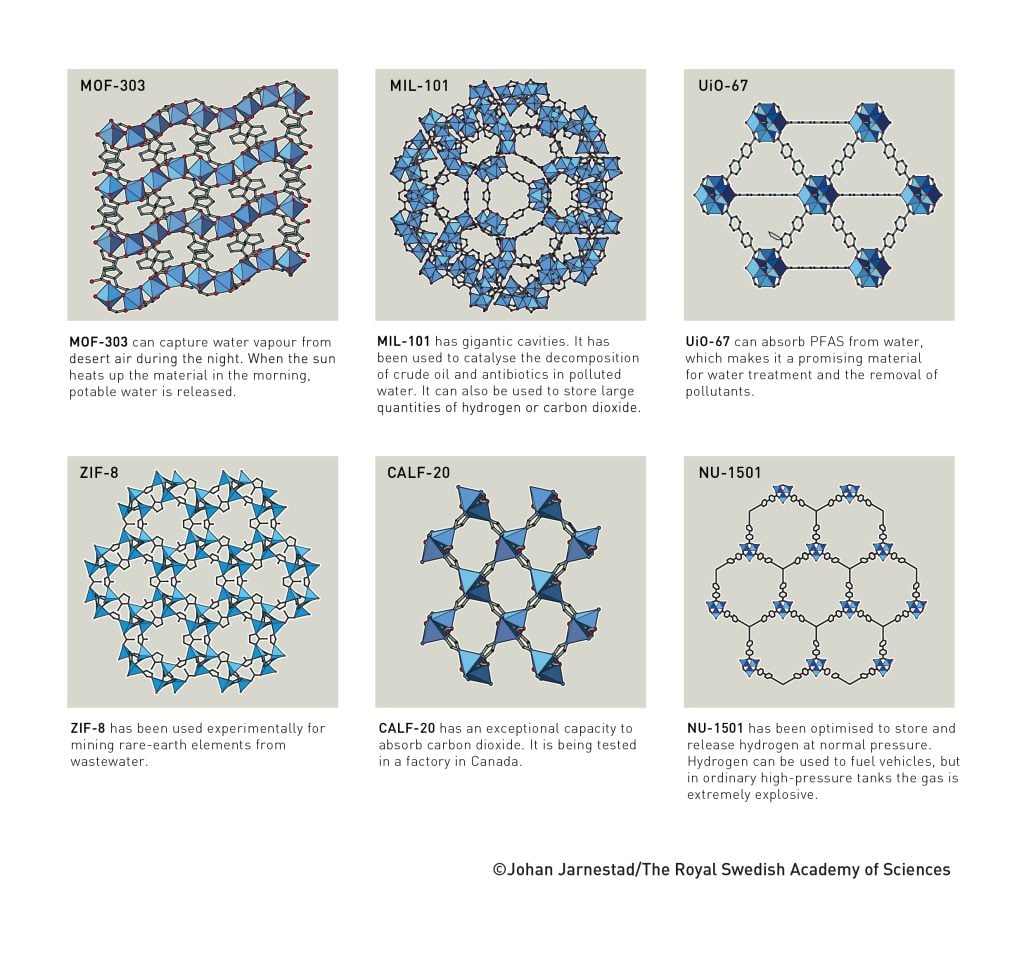

These remarkable materials can be thought of as molecular sponges or programmable crystals. Built from metal ions and organic linkers, their defining feature is a vast internal porosity, allowing just a few grams to have a surface area the size of a football pitch. This unique property has unlocked potential solutions to some of humanity’s biggest challenges, from capturing carbon dioxide and harvesting water from desert air to filtering pollutants and delivering drugs.

Figure Caption: The versatility of MOFs is staggering. Different frameworks are tailored for specific tasks, such as capturing water from air (MOF-303), storing hydrogen fuel (MIL-101), removing PFAS pollutants from water (UiO-67), and absorbing industrial CO₂ emissions (CALF-20), showcasing the breadth of research built upon the laureates’ foundational work. (Note: The image above is a placeholder representation of Figure 7 from the Nobel source text. You can replace the URL with the direct link to your desired image.)

The laureates’ journey is a story of visionary science. It began with Richard Robson’s foundational idea to build large, ordered networks. Building on this, Susumu Kitagawa developed the first stable, functional MOFs and crucially envisioned them as flexible structures that could “breathe.” Omar M. Yaghi then perfected the field by demonstrating a “Lego-like” approach to their creation, allowing chemists to rationally design frameworks with tailored properties, including his iconic and exceptionally spacious MOF-5.

This tale of three pioneers seems like a classic case of the “Newtonian” view of science—that progress is driven by a few brilliant giants who provide the shoulders for others to stand on. However, the story of MOFs also powerfully illustrates a competing idea: the Ortega hypothesis [2]. This theory suggests that major breakthroughs don’t happen in a vacuum. Instead, they arise from the slow, cumulative, and often anonymous contributions of a great number of working scientists.

This is where Susumu Kitagawa’s personal motto—to find “the usefulness of useless”—becomes profoundly insightful. Science is filled with countless small experiments and niche discoveries that seem purposeless in isolation. The Ortega hypothesis argues that progress depends on this vast, unglamorous foundation of “useless” knowledge. It’s an ecosystem of modest findings that a few brilliant minds can eventually synthesize into a revolutionary concept. The laureates themselves were building on decades of fundamental chemistry. Kitagawa’s philosophy wasn’t just a personal quirk; it was an acknowledgment of the very nature of scientific progress.

We see this process in action right now. Today, labs across the globe are using the MOF toolkit to design countless specialized frameworks [3]. Each team works on a narrow problem—a single pollutant, a specific gas, a unique catalyst. Each contribution is a small, vital step forward, an anthill of progress built upon the architectural plans the laureates drew.

The laureates’ work defined a design space so vast it became a big data problem, which global research has populated and AI can now analyze.

Instead of relying on slow physical synthesis, AI models computationally screen millions of potential MOFs to pinpoint the most effective candidates for tasks like carbon capture. This is the new paradigm for discovery: human genius creates the field, collective effort generates the data, and AI provides the scaling engine to find the solutions within.